Mary was born on March 18, 1597 in the tiny village of Fairstead, Essex, England. She was the ninth out of the thirteen children born to Henry Robinson and Elizabeth Orvice. As Henry was the rector of Fairstead parish, one might describe Mary as a "PK"--preacher's kid--if she had lived 400 years later in the 21st century. Mary's siblings (in order) were Jane, William, Elias, Michael, Elizabeth, Margery, Reuben, Anne, Henry, Deborah, Priscilla, and Martha; their births spanned 23 years, from 1582 to 1605.

At 24 years old, Mary married Thomas Birchard, also of Fairstead. Mary and Thomas were Puritans, which meant that they protested the Church of England on a number of issues ranging from theology to ethics to politics--remember that church and state were closely wedded in early modern England. All of Mary and Thomas's seven children were born in Fairstead. They were Elizabeth (1621-1699), Mary (1623- ), Sarah (1624-1659), Susannah (1626- ), John (1628-1702), Deborah (1632-1633), and Hannah (1633- ).

|

| St. Mary Church, Fairstead, Essex, England. This church dates to about the year 1200. Mary grew up attending this church where her father was the rector. Mary and Thomas were most likely married in this church. For more exterior & interior pictures, click here. (Source: essexchurches.info) |

Two years after Hannah's birth, Mary and Thomas made the momentous decision of emigrating to New England. John Winthrop and the first waves of Puritan migration began in 1630. Even earlier, a small number of Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts in 1620. Thus, Mary and Thomas were not among the first Englishmen to arrive in New England. Many of the unpredictable factors that vexed the first immigrants to the New World, such as a new climate and successful agriculture, must have been well-established knowledge by the time Mary and Thomas boarded the Truelove in London on September 19, 1635. The Birchard family represented eight of the 67 passengers in total aboard the Truelove. At fourteen years, Elizabeth was the oldest of the children and was no doubt tasked with helping to care for the youngest of the children--Hannah was only two years old.

Mary, Thomas, and their children must have arrived in America well before the end of 1635. Thomas and Mary were admitted as a members of the church in Roxbury, Suffolk, Massachusetts before the end of the year. However, they did not long remain in Roxbury. Sometime before February 1639, the family moved to the new town of Hartford, Connecticut. Hartford was less than two years old when the Birchards arrived. Thomas immediately began accruing land. In 1639, he owned five lots totaling more than 35 acres. It is Thomas's extensive land investments, his literacy (he signed land deeds himself), and his service as deputy to the Connecticut General Court that all belie the Truelove record stating that he was a laborer by occupation.

|

| The rough location of one of Thomas Birchard's properties in Hartford, Connecticut in the late 1630s. His house faced what is now Trumbull Street, where the Hilton Hartford now stands. |

By overlaying a 1640 property map of Hartford onto Google Earth, I was able to locate where the lot with Thomas's house was. The house faced present-day Trumbull Street. It was on the west side of Trumbull where the Hilton Hartford hotel now stands. Thomas's land extended back from Trumbull about two present-day blocks to what is now High Street, and covered about five acres. I'm pretty certain that all traces of the Birchard family have now vanished! But I'd still like to go check it out someday.

The Birchards next moved to Saybrook, Connecticut. In 1650 and 1651, Thomas was one of two deputies representing Saybrook at the Connecticut General Court in Hartford. Thomas evidently had experience as a surveyor; he and the other Saybrook deputy, John Clarke (who was also his next-door neighbor in Hartford), were tasked by the General Court with helping to settle a land dispute between Pequot Indians and English veterans of the Pequot War by surveying and appraising several large tracts of land.

Thomas and Mary did not remain for long in Saybrook. By late 1652, they had removed to Martin's (now called Martha's) Vineyard. Edgartown, Dukes, Massachusetts property deeds from December 1652 reference land that Thomas owned on the "Great Harbor." In a sign of his growing wealth, despite moving to Edgartown, Thomas retained ownership of land in both Hartford and Saybrook. In fact, records show that, in the interest of his land, he attended a Saybrook town meeting in January 1656, long after he had moved to Edgartown. Thomas also quickly became a leading citizen in Edgartown, performing surveying work for the town and serving as its first town clerk (1654-1655).

Thomas Birchard's wealth and social standing as a civic leader provide a small indicator of what Mary's life was like. Whether on civic or personal business, Thomas traveled frequently. Commenting on "gender ways" in Puritan culture, the historian David Hackett Fischer argues in Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America that there were no "separate spheres" of domestic activity between men and women. Husbands and wives both worked the tasks--which were arduous and voluminous--required to maintain a 17th century American household. If a husband, for whatever reason, was not available to perform domestic chores, his wife and children picked up the slack. Fischer writes, "Depositions filed in the court of Essex County, Massachusetts, during the late seventeenth century describe women routinely doing heavy field labor, carrying sacks of grain to the mill, cutting firewood, tending swine, and castrating steers. One minister wrote that a woman 'in her husband's absence, is wife and deputy-husband.'" (Fischer, Albion's Seed, 85) With her husband so often away from home, Mary must have been just such a woman.

Little evidence of Mary's life has survived. We can only guess at her life from generalities that historians have constructed about Puritan women's lives. For an analysis of these generalities, I refer again to Fischer. Puritans adhered to a strictly conservative interpretation of a husband's authority in the family. However, in other aspects of women's lives, Puritans were quite progressive. Men and women were thought to have spiritual equality in the church, yet women were not able to become ministers or preach to anyone other than other women. Husbands, except in cases of being deceased, were the property owners in families. But wives were not considered the property of the husband--they had a legal right to physical and emotional protection from abuse. Finally, there is ample evidence that Puritans' marital ideals involved love between a husband and wife. Many examples survive of spousal correspondence that imply loving, respectful relationships. Fischer outlines these points and more in Albion's Seed, a book worth reading if you'd like to know more about the everyday lives of Puritans--how they spoke, dressed, raised their children, and much more.

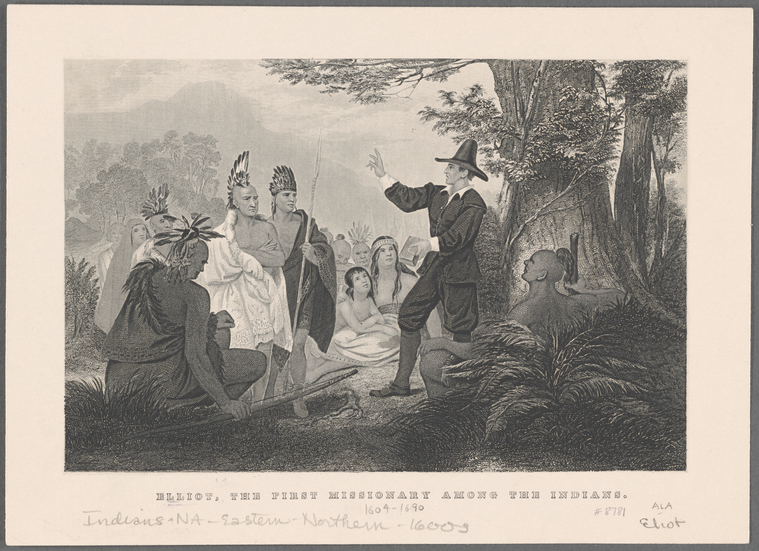

Mary passed away on March 24, 1655. Genealogists are uncertain whether Mary died in Roxbury, where her death is recorded in church records, or in Edgartown, where she and Thomas were living at the time. Despite spending most of their time since moving to New England in Connecticut and Martha's Vineyard, Mary and Thomas maintained the relationships they'd developed in Roxbury in the 1630s, particularly with Roxbury minister Rev. John Eliot. Mary may have passed away in Roxbury while visiting old acquaintances--and thus had her death recorded in church records there. Alternatively, she may have died in Edgartown and had her death recorded in Roxbury records due to her and Thomas's ongoing relationships with people in Roxbury. Among the evidence supporting the latter interpretation is the fact that Thomas maintained correspondence with Rev. Eliot over the years after his departure from Massachusetts. Because Thomas remained on familiar terms with Rev. Eliot, he may have written to the minister upon his wife's death. This would explain why Mary's death was recorded in Roxbury church records. There is no definitive answer to where Mary died, whether Roxbury or Edgartown.

Mary (Robinson) Birchard deserves to be remembered by her descendants for the courage and personal strength she demonstrated in seeking a better life for her family in the New World. While the desire to practice her Christian beliefs in a "purer" manner was undoubtedly the chief factor in her decision, other reasons for English migration included economic rationales--e.g., inexpensive land. In any case, Mary was willing to make an arduous trans-Atlantic voyage with six children at the age of 38, all for the betterment of her family.

Mary was my 11th great-grandmother. If you're interested in viewing the family tree I've created on Ancestry.com, please send me an email; it's easily shared!